Detecting Election Fraud and Responding to it

How can we process potential election fraud and what can be done to undo an election?

Hi Friends:

Since people were asking me this question a lot, I decided to take it up now as a separate post. I will also apologize for a gap of posts (even though I have a lot of partial posts in process) because I had total knee replacement surgery and was out of my mind for a while.

Our Situation

Our team has been working steadily to develop effective methods for identifying potential election anomalies — particularly those that might suggest fraud or systemic error. Our goal is to establish a quick and reliable check to flag when something looks “off” in the results, especially when compared to historical voting patterns and expectations.

One of the primary tools we’ve employed is Precinct Deviation Analysis (PDA), which comes in several variations. PDA focuses on identifying unexpected turnout levels or shifts in vote margins at the precinct level — the smallest reporting unit — to spot irregularities that may warrant further investigation. Importantly, this method can detect some types of fraud that are undetectable by Risk Limiting, ballot image or other audits.

Our most concentrated work has been on Clark County, Nevada, which accounts for about 66% of the total vote in the state. Notably, although Harris won Clark County in the 2024 presidential election, the overall statewide result flipped from a Democratic win in both 2016 and 2020 to a Republican win in 2024 — by a margin of just 46,000 votes. So it was an obvious place to start and learn as much as we could.

What we observed through PDA is that turnout in D-leaning precincts appeared to be unusually low, raising concerns that either ballots were not properly counted, voters were disenfranchised, or turnout was suppressed in ways that do not align with expected trends.

You can take a look at these posts to refresh your memory:

https://substack.com/home/post/p-152243533 "Nevada 2024 Partisan drop off"

https://substack.com/home/post/p-154291476 "Convincing evidence of likely manipulation of 2024 Presidential votes in Nevada" (newly updated)

https://substack.com/home/post/p-156436516 "Estimated Lost Votes in Clark County by Precinct Deviation Analysis (PDA)"

I have updated the “Convincing Evidence” post with plots of the same county in prior elections, were the “droop” in the D-leaning precincts does not exist or at least is a lot less pronounced.

I will be soon posting deep dive into our further research which should be out soon, but I may have to split it up to meet length limits.

Part I: Evaluating potential indications of fraud

Making claims that fraud can be proven is a pretty high bar — and rightly so. Even our recent "Convincing Evidence" post stops short of making that assertion outright. We’re still in the evaluation phase, and it's important to distinguish between a plausible anomaly and conclusive proof. Other groups have also surfaced claims, some suggesting that the Trump campaign — possibly in coordination with technically sophisticated allies like Elon Musk — may have found a way to manipulate the results. Regardless of the source, any such claims must be subjected to a methodical review to determine whether they are credible, coherent, and supported by verifiable data.

Step 1: Sanity Test

The first step is simple but essential: Does the claim even make basic sense?

This step asks whether the evidence being presented aligns with public, independently accessible data, and whether it is logically sound. Many claims fall apart here — not because they are malicious or deliberately deceptive, but often because they’re based on a misunderstanding of election processes, data sources, or terminology.

For example, one group claimed:

“The abortion ballot question received more votes than all presidential candidates combined.”

This is a straightforward claim that we can test using official election results. If the numbers don’t bear it out, the claim is false — and should either be corrected or set aside. If clarification can’t be provided, it’s not worth further pursuit. (And so we set this claim aside because it did not make sense, and the maker of the claim did not attempt to clarify.)

A notable case of this kind of failure occurred during the Maricopa County, Arizona “audit” conducted by Cyber Ninjas. They claimed that there were 76,000 more ballots processed than there were voters on the voter list. At face value, this would be a massive red flag — if true. But the claim was based on a misunderstanding of which version of the voter list was being used.

The list they referenced was a static snapshot used during the election for Get Out The Vote (GOTV) efforts — specifically, to help campaign volunteers target voters who had not yet cast a ballot. That list was no longer being updated late in the process, because the GOTV campaign was already over. So the mismatch they pointed out was not fraudulent; it was an artifact of using the wrong version of the data. Election officials explained this, but the original claim was still widely circulated and tweeted as fact — long after it had been debunked.

(That said, this list should reflect the final numbers so this comparison could be made, and it was put forward by Sen. Ken Bennett in Arizona as a reform to improve the process. While the bill was not approved due to other issues, it’s possible that the list is being improved nevertheless.)

After the 2020 election, Edward Solomon, Beadles and “Operation Sunlight” offered $50,000 if you could prove that their claims were incorrect. We looked into this because the money seemed worth a little time. But in the end, it was just a big circular hoax, which I can summarize their broken logic. They said:

We believe the results in the 2020 election in NV were hacked by the Biden campaign.

Therefore, we will consider Will County in Illinois.

And prove that there is self-consistency of the numbers there, such that we can model the relationship between the in-person and mail voting using a cubic spine curve fit.

And the curve fits so well that it could not be due to natural causes.

And therefore, even though this is not even in NV, the results in NV are fraudulent.

I kid you not. They create a quagmire of mathematics and definitions, but then boil it down in their spreadsheet to a cubic spline curve fitting. If you can make it through their misdirection and unusual definitions you get to a simple cubic spline curve fit and the notion that “if fits too well, and therefore must be fraudulent.” This conclusion has no support. Consistency within the numbers in Will County, IL does not mean it is fraudulent and that does not mean Clark County NV is also fraudulent. I guess you know they had no intention of ever admitting that the claims were simply silly, and no one got the $50K, but today, they still say: No one was able to prove us wrong! (I did spent far too much time on this one.)

But this does point something out that is pretty important. We need a method that can be easily understood. That means a visualization is required and it must be easy to see possible fraud.

Step 2. Independent Analysis

If a claim relies on a statistical model or visual representation, it's critical that independent analysts replicate the analysis to verify the results. This process ensures that the outcome is not simply the result of a coding error, a misunderstanding of the data, or selective interpretation.

In the case of our “Convincing Evidence” Precinct Deviation Analysis (PDA) plot, multiple independent analysts accessed the same underlying election data and replicated the findings using their own code and methods. Their confirmations strengthen confidence in the accuracy and validity of the original analysis — and reinforce that the visual pattern we highlighted is not an artifact of error.

Bullet Ballots Theory was False

Contrast that with the so-called “bullet ballot” theory, originally promoted by Stephen Spoonamore. This theory was presented as a potential explanation for the partisan drop-off observed in some precincts — where voters purportedly selected only a presidential candidate but left the rest of the ballot blank. However, the supporting claims did not hold up under scrutiny. Once the data was reviewed more closely1 , it became clear that the pattern described simply wasn’t present in the actual vote records, and the theory collapsed under the weight of its own inconsistencies. We will give some credit to Spoonamore for at least retracting his claims but certainly his reputation is at least partially damaged. (And now I hear he has retracted his retraction. But we looked at the data and there are some bullet ballots, but not an unusual number, and about the same number for Harris as for Trump)

Independent analysis serves as the guardrail against both unintentional error and overconfidence in compelling — but unverified — narratives.

Step 3. Visualization or Statistical Related Misconceptions

Several popular methods for visualizing election results can unintentionally — or sometimes deliberately — distort the public’s understanding of what actually happened. These methods often convey strong visual impressions that are not supported by the underlying data. Here are two of the most common examples:

Choropleth maps

A choropleth map2 uses shading or coloring to depict the distribution of a variable across geographic regions, such as states or counties. While useful for many purposes, these maps are often misleading when used to present election outcomes.

For instance, coloring states red or blue by majority vote creates an image where vast areas of the country appear bright red — implying overwhelming support for one candidate. But area is not a variable in the election; population is. Large but sparsely populated states like Wyoming and Montana carry the same visual weight as densely populated states like New York or California, which skews perception.Only 175 counties out of roughly 4,500 contain half of the U.S. voting population — but that fact is completely lost in a traditional red/blue state map.

Typical map of the results of the 2024 election make it appear that a Trump won a much stronger mandate than he actually did— despite winning by just a 1.5% margin in the national popular vote between Trump and Harris This issue was examined in depth by Mark Monmonier in “How to lie with Maps”,3 where he wrote:

“Not only is it easy to lie with maps, it is essential. To portray meaningful relationships for a complex three-dimensional world on a flat surface, a map must distort reality... While most map users willingly tolerate white lies on maps, it’s not difficult for maps to tell more serious lies.”

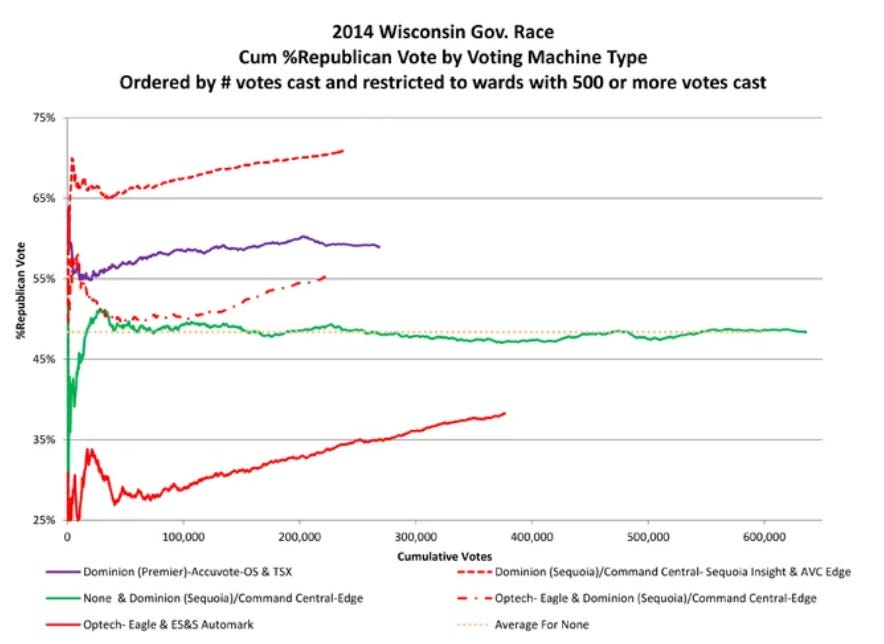

Cumulative Vote Totals (CVT) charts.

CVT charts are another visualization tool that has led to widespread confusion. These plots typically:Place precincts on the x-axis (usually ordered from small to large),

Show the cumulative vote margin on the y-axis.

The claim made is that once enough votes are counted, the margin should stabilize — and any deviation from that is suspicious. But this assumes that precinct size is correlated with vote behavior, which is not always true.

Larger precincts often differ demographically or geographically from smaller ones, so their inclusion can legitimately change the margin. Worse still, many people misinterpret the x-axis as a timeline, speaking of the chart as if it shows the election unfolding over time — when in fact it may be simply ordered by size, not by when votes were counted.

This visualization gained popularity in 2020, especially in analyses by Jeffrey O’Donnell, also known as “The Lone Raccoon.” His 281-page report, The Fingerprints of Fraud, relies heavily on CVT plots to argue that every district in the country was compromised. I made a YouTube that reviews his claims. He describes the plots as if they are related to time, even when he inverts the x-axis and shows it in the other order. The ordering he uses is never precisely described. He may incorrectly use the order in the Cast Vote Record, which is not correlated with time, and again, can be easily misinterpreted.

While the methodology is deeply flawed and fails to account for the statistical nature of precinct-level data, O’Donnell did provide a valuable public service: his collection of Cast Vote Records (CVRs) was assembled by university researchers into one of the largest open datasets of from across the country, now housed in the Harvard Dataverse.4

Although his conclusions are incorrect, the effort to collect and release CVRs has been a significant contribution to public transparency and research on election integrity.

Step 4: Evaluate the Anomaly

Once we've ruled out basic misunderstandings, visual distortions, and analytical errors, the next step is to evaluate the anomaly itself. Specifically: Can the observed deviation be explained by any plausible cause?

We typically break possible explanations into three categories:

Known and proven natural causes

Hypothetical (but unproven) natural causes

Hypothetical errors or malicious causes

A common fallback explanation for the 2024 election is something like:

“Democrats just didn’t show up to this election — that’s why they lost.”

This would fall under a hypothetical but unproven natural cause. It's plausible — but is it true?

To evaluate this, we turn to the data. In our Precinct Deviation Analysis (PDA), we found that turnout between the two parties was nearly identical overall. However, when we looked at D-leaning precincts, we noticed that the total turnout (votes cast for any candidate) was lower than in R-leaning precincts. In other words:

D-leaning precincts showed lower overall turnout (of both parties)

Within those precincts, Democratic and Republican voters turned out at roughly equal rates, when compared with the number of registered voters.

So it’s not accurate to say that "Democrats didn’t vote." Rather, it may be that ballots from D-leaning areas were not fully processed, or there are more inactive voters in D-leaning precincts than in R-leaning precincts. Those hypotheses — while still under investigation — fits the data more closely than the vague assumption of voter apathy.

It’s critical that reviewers do not accept unproven natural causes as definitive explanations just because they sound reasonable. Even if a natural cause could explain the result, the actual evidence must support it.

Likewise, even in the presence of natural explanations, certain specific statistical or geographic patterns might be more consistent with the actions of a malicious actor. For example, if uncounted ballots or turnout suppression are clustered tightly in specific precinct types — and those types strongly correlate with one party — the anomaly may warrant closer scrutiny for intentional interference.

We don’t need to jump to conclusions. But we do need to weigh the plausibility of all causes — and match them to the patterns in the data.

(I will publish a deep dive into the PDA results in Clark County soon).

Part II: What can we do?

1. Immediately after the election

One of the main goals of Precinct Deviation Analysis (PDA) — or any post-election statistical review — is to provide a rapid, credible, and data-driven evaluation of whether the results seem legitimate or if something appears to be amiss. We also want to include the chance that ballots may have been suppressed before being cast. This type of fraud is not detectable by tabulation audits, which compare the actual ballots accepted as cast with the final results.

Contesting the election in court

This early evaluation is not just academic — it has real-world legal implications. In most jurisdictions, any formal election contest must be filed within days of certification, and the right to file is typically limited to a candidate or their campaign. The deadline is strict and the window is short.

In terms of legal mechanics, the process to initiate a contest is surprisingly simple: in many cases, it’s just a brief letter stating that the candidate is contesting the results. The processes vary by state, but I have been through this myself in California and am familiar with how it works in practice.

To go beyond the initial filing, however, and reach a discovery phase, the plaintiff must present a specific, plausible basis for challenging the results. This is where analyses like PDA become critical — they provide targeted, statistical indicators that can justify further scrutiny of the results, precinct-level behavior, or specific voting equipment.

More often than not, any court proceeding will be stopped dead it its tracks at this point, due to a technicality, like standing, whether there is a remedy, or the idea that the plaintiff did not prove that there was a problem with the outcome. Yes, that’s right, you have to prove it sufficiently to be able to get started and look at any further evidence.

Recounts are an Alternative Path

In addition to legal contests, there's another path available in most states: the recount.

Recounts are not handled by the courts but are part of the standard election procedures. A candidate or campaign can request a “recount” which may be a manual hand count of the results, and in some states, it is just a machine recount. If the recount reveals a result-changing error, the county typically bears the cost. But if the result stands, the requester is responsible for the full cost — which can be substantial, particularly in large counties, and also if the physical ballots are not sorted by precinct.

This cost barrier makes it even more important to have a fast, accurate, and publicly credible method of assessing whether a recount is warranted. Without data-driven suspicion, most candidates are understandably reluctant to fund a recount effort on vague doubts alone.

The Role of the Candidate — and the Problem of “Conceding”

Because these legal options are frequently only available to candidates or campaigns5, it's crucial that any statistical findings or irregularities are communicated to them before key deadlines pass. Unfortunately, modern political culture places tremendous pressure on losing candidates to concede quickly, as a show of unity or to avoid being seen as a "sore loser."

But legally, conceding has no effect. The outcome becomes final only after the results are certified and the challenge period ends, or after courts resolve any contest.

There is no legal requirement to concede — and in situations where anomalies are present, withholding concession until a proper evaluation is complete is a prudent and responsible course of action.

Actually, candidates and campaigns should avoid conceding and wait for all audits to be completed and the results certified, no matter how large the margin may seem, and no matter what sort of pressure they may feel.

2. After Certification (but still rapidly)

Once the election has been certified and the official challenge period has passed, it is technically no longer possible to change the results — at least according to most legal interpretations.

But in practice, that’s not entirely true.

A striking example occurred in Monmouth County, New Jersey, where an objection was raised after certification by a concerned citizen — someone who was not even on the ballot — simply because the results “did not look right.” Upon investigation, it was discovered that election staff had accidentally read the media from seven voting machines twice, and the election management system, shockingly, treated those double-read ballots as new ballots and assigned them new serial numbers.

This error added 977 extra ballots to the tally and directly impacted multiple contests. A recount was ordered, and in at least one race, the outcome changed.6

The lesson: Anomalies can be corrected post-certification — but only when credible concerns are raised quickly and taken seriously. That makes early detection and communication absolutely essential, even after the official window has closed.

3. Much Later

In the case of a presidential election, there is currently no established legal pathway to undo the results — no matter how compelling the evidence may be, except through an impeachment process.

Even if it becomes clear that the outcome was more likely the result of malicious interference than natural causes, the courts are unlikely to act. Why? Because they typically require not just a harm, but an available legal remedy. And when it comes to a seated president, particularly Donald Trump, it is highly improbable that the Department of Justice — under its current leadership — would entertain any attempt to overturn the result.

This is the unfortunate legal and political reality we face.

My experience tells me that even if such a legal mechanism existed, it would rarely be effective. Legal challenges are time-consuming, costly, and often a nonstarter. How long did it take for the Dept of Justice to complete proceedings into actions after the election by Trump and his campaign? Nearly the entire four yeas of the Biden administration.

Such cases tend to stall or backfire — and unfortunately, many organizations raising funds for such efforts are either misguided or misleading. As of now, Harris is not contesting the outcome, and the Democratic Party is not aligned on any legal strategy to challenge the result. So if someone says they are raising money for a legal challenge, it is most likely just grifting.

The Power and Wisdom of Crowds

So what can be done?

We must turn to the power of the people — the wisdom of crowds. When people work independently but with a shared purpose, their combined impact can be surprisingly powerful7. You can become a member of protests and rallies. Don’t underestimate the power you have when combined with others of the same mindset. Don’t wait to be told what to do. Put on your thinking cap and take action, but stay within legal bounds and avoid violence.

We’re now beginning to see signs of change. Even former Trump voters are waking up to the disconnect between promises and outcomes. He did not lower prices, he did not solve the war in Ukraine in 24 hours, and he’s already imposed tariffs that will destabilize long-standing international trade agreements in ways that are hard to predict. A full recession or depression may be around the corner. Even the conservative-leaning Wall Street Journal has begun raising the specter of impeachment.

To harness this momentum, we must each do everything we can, as aggressively as we can. If you can join a protest — do it. If you can contribute to data analysis or amplify credible findings — do it. And above all, help spread the word that it is not yet proven that Trump, Musk, and others did not manipulate this election. The burden of proof must go both ways.

A Note on the Idea of a General Strike

Some have proposed a general strike — a coordinated shutdown of economic activity — as a way to apply pressure to political leaders and signal mass dissent. In theory, such an action could force attention to issues that are being ignored or dismissed.

But in practice, a general strike is extremely difficult and risky to execute effectively. Unlike traditional labor strikes, most participants in a general strike would not be backed by unions, would not have legal protections, and would personally bear the economic cost — often those least able to afford it.

Even more importantly, a general strike presumes that those in power care about economic disruption or fear the consequences. But in this case, Trump has already created significant economic instability through tariffs and policy shifts, and if a general strike were to occur, the resulting disruption would likely be blamed on the strike itself — not on the underlying policies that caused the decline. The protest might be dismissed outright, while its economic consequences are weaponized politically to deflect blame and further entrench power.

For these reasons, I do not believe a general strike is a wise or effective strategy in this moment.

Consider Targeted Boycotts Instead

That said, targeted boycotts can work. They apply pressure selectively, can be more easily coordinated, and allow participants to retain agency over their level of involvement.

Targeted action focuses energy where it can do the most good — without broad collateral damage. It's a strategy worth considering as part of a larger grassroots effort.

4. For the Future

From what I’ve seen, lawsuits rarely produce meaningful change — and often harden opposition. The courtroom is an adversarial arena, and once legal positions are staked out, compromise becomes nearly impossible. That’s why courts are generally a poor venue for reform.

While courts can rule that a government action violates existing law, they cannot create new laws or mandate systemic improvements. So even if a lawsuit succeeds, it often doesn’t move things forward — it can only stop what’s already happening. If you're suing the authorities, you're not building something new — you're just trying to block what’s already been done.

But that doesn’t mean we’re powerless.

Sometimes, the simple act of putting evidence into public discourse — even in the context of a failed lawsuit or public hearing — can change minds, shift narratives, and lay the groundwork for reform. Legislative change is a viable option, but it’s often highly contentious. Too often, bills are drafted at ideological extremes, loaded with “poison pills” designed to ensure failure — not passage. This allows politicians to blame the other side for inaction while scoring points with their base, rather than building real consensus.

A Path Through Technology and Transparency

Election officials may adopt better practices simply because they work. Personally, I find these opportunities the most productive — they allow us to push for change by example rather than confrontation.

One such opportunity lies in the realm of election auditing. While many current audit practices are weak, opaque, or easily manipulated, audits run well can help. I’ll soon be publishing more about the deep flaws in Risk-Limiting Audits (RLAs) — particularly in Nevada, Pennsylvania, Arizona, and other states — as well as how they can be improved and how Ballot Image Audits can supplement or replace them.

A truly bad audit can be worse than nothing, as it may give false reassurance without real accountability.

Our current focus — building tools for fast, reliable evaluation of election outcomes using public data — may be the most critical challenge we face right now. We’re not giving up.

Prior Post: https://substack.com/home/post/p-159096971 Ridiculous Issues in Dominion Voting System Certification in California

All posts: https://substack.com/@raylutz/posts

“How to Lie with Maps”: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MwdRDwAAQBAJ

Not always true. In CA, any member of the public may file a contest of the results, but it is very hard to get past motions to dismiss by the county or state.

See https://copswiki.org/w/pub/Common/M2009/2023-07-04%20M2009%20NJ%20--%20Three%20County%202022%20Audits.pdf “Ballot Image Audits of: Burlington, Mercer and Monmouth Counties (2022) New Jersey” page 3. The Ocean Township school board results were incorrect and the outcome was flipped

I will soon publish “The Parable of the Snake River Rocks” on this substack, where I learned a profound truth about how people will perform work without being directed if they have a common goal and they can see that they can make even a small incremental change with each action.

Seems like a perfect crime. If you get away with stealing an election for a few months you “win”.

It seems to me that legal cases, even this late in the day are worthwhile, because they give an excuse for the media to ignore their usual anticipatory obedience to Trump, and publish it as newsworthy. This meshes with your next point about protests.

How much greater would the protests be if there was general knowledge that Trump’s gang usurped the democratic choice and stole the Presidency. It’s not the long wait for a court case’s outcome necessarily, it’s the public pressure that results from the case itself and that pressure could carry even to the Supreme Court.

Trump’s chaos, his prior insurrection ineligibility, election fraud, pardons of convicted insurrectionists (giving aid and comfort being an insurrectional deed), not governing in a “Republican form of government”, violating the Constitution in many other ways, may in the end force the Supreme Court to require a 2/3rds majority of Congress for Trump to continue or otherwise hold a revised electoral college vote.

That’s why we should all get behind Election Truth Alliance and pressure for forensic audits in areas they have identified, like in Pennsylvania. It’s too important to not all be pulling together at this point, with USA democracy almost lost to fascism.